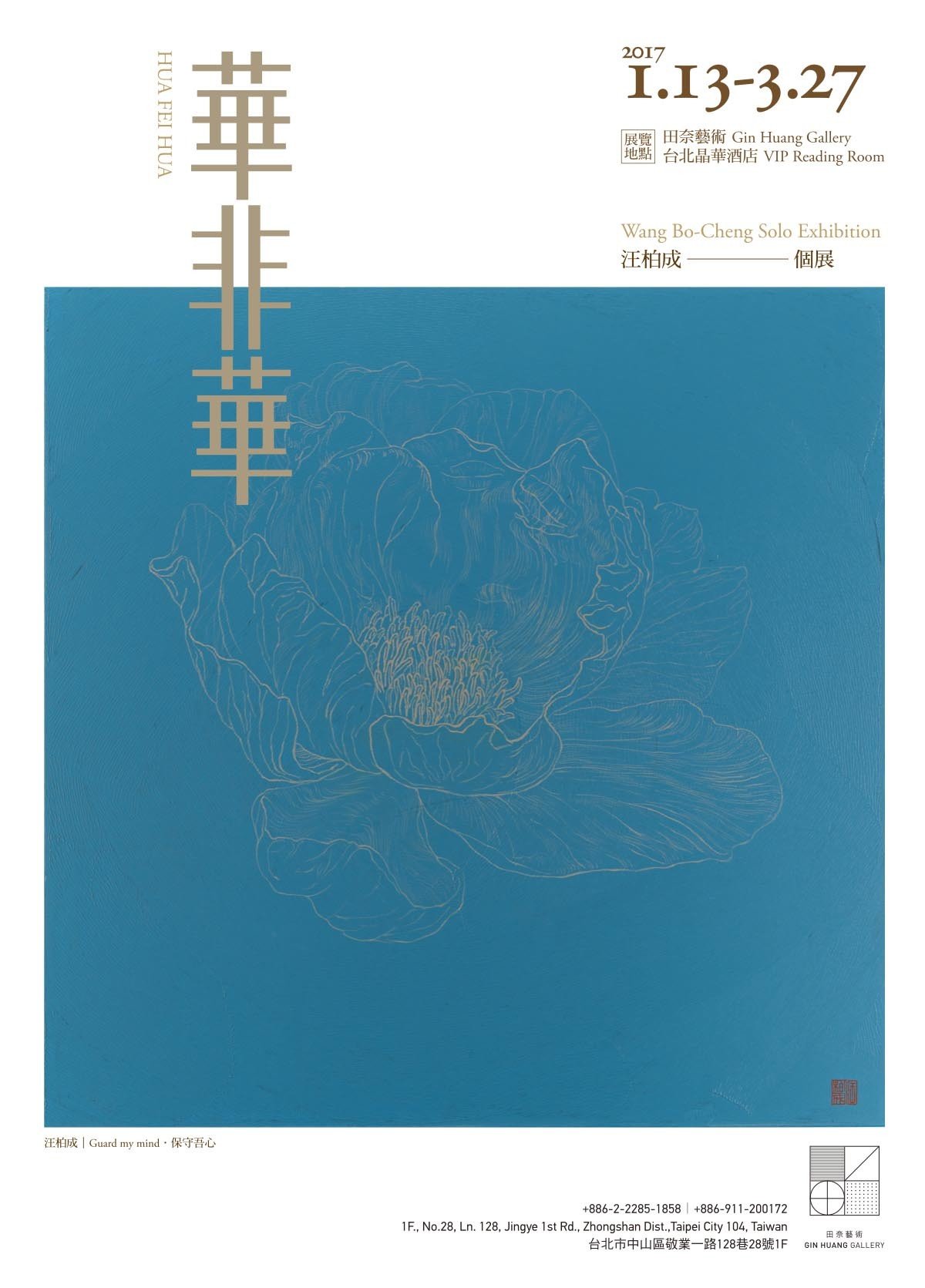

Observation and Inspection-Wang Bo-Cheng's Latest Solo Exhibition ''Hua Fei Hua'' Dharma and the Art of Calligraphy.

這裡是標題,程式會自動抓

Dec., 01, 2016

Prior to becoming an artist, Wang Bo-Cheng had been a practitioner of Buddhism for three decades and a calligrapher for 24 years. Wang is an introvert and has always expressed his emotions through paintings since childhood. Although Wang grew up in a military family of rather conservative values, his father has been fully supportive of his passionate creativity. Wang entered an art-specialized class in high school, started creating sculpture artworks in university, and continued pursuing graduate studies from Graduate Institute of Architecture at National Chiao-Tung University. Currently, he is a professional architect, master of seal cutting, and the founder of To Hei Chinese Calligraphy Association. Both of his parents are pious Buddhists and advocates of Chinese culture. Thus, Wang has been immersed in Buddhism and calligraphy since three years old. With his continuously attentive practices, Wang draws his inspiration of the artistic creations from Buddhism concepts and the philosophy of calligraphy in his early thirties. Standing at the intersection of the three seemingly parallel paths, Wang combines all the elements from Buddhism, calligraphy, and architecture in his artworks. The shy boy is now speaking out loud with his contemporary arts, expressing them through ancient Buddhism and the withering art of calligraphy. His simplistic and sophisticated style resembles Buddha’s philosophy; his natural flow of strokes manifests the incarnation of calligraphy. We experience the grandeur of contemporary arts through Wang’s pieces. His artworks transcend the boundaries of time which allow the past and the future to intersect at this moment, as how he puts it, “Classics is modernity.”

Abstract Divinity and Mandala Perspectives

Wang began his solo exhibition since 2013 and later on published the “Transformation” collection. Artworks such as “Between,” “Core,” “Practice,” and “Imperfect” are the extension of this collection. “Hua Fei Hua” also derives from “Tongpa,” which is one of the pieces in “Transformation” collection. Observed from the visual standpoint, “Tongpa” and “Hua Fei Hua” have almost nothing in common. “Tongpa” expressed the concept of “Everything visible is unnamable” in "The Maha Prajna Paramita Hrdaya Sutra" through seal cutting. The organization of the words as a QR code gives it the look of an abstract geometric totem. However, the core contents are in fact the scriptures that are able to be discerned and recited. These semiotics in the digital era reversely reflect “the surface” and “the core” as well as “the vanity” and “the truth” in our universe. “Hua Fei Hua” illustrates the flowers without stems and leaves floating in the air with semi-abstract line drawing technique. The ideologies are delivered through concrete objects. Such method metaphorically shows the Buddhism perspectives in the Mandala world. Concepts of “Everything is destined” and “To see a world in a grain of sand” are re-presented. The collection explores the many facets of human relationships and human nature.

If “Hua Fei Hua” is evaluated by the visual analysis in art history, the outcome should be disappointing. Its intended simplified form is unable to directly implicate the grand structure of metaphysics behind it, just as the divinity not fully presented in the geometric arts by American abstract expressionist Mark Rothko. Rothko once said, “I'm not an abstractionist. I'm not interested in the relationship of color or form or anything else. I'm interested only in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on.” Rothko does not explore form in his creations, although he chose or was included in, the field of abstract expressionism, which is a genre susceptible to form discussion. Yet, he remained in pursuit of the spiritual or emotional signified objects. This idea could be exemplified in the large-scale painting he did for Rothko Chapel. Despite being named as chapel or church, Rothko Chapel was designed without any decoration of Biblical stories or religious images. The only spiritual emblem is Rothko’s abstract artworks. Using “nothing” to represent “everything,” the design circumvents the taboo of taking substances to refer deities. The abstract divinity in Rothko Chapel fulfills the lack of the concretized divinity. Buddha holds the flower and Mahakasyapa smiles. The truth expressed through nothingness in Buddhism is subtle yet magical. The reason not to pass down Buddhism through words is because no words could explain the truth. “Hua Fei Hua” uses elegant flowers like lotus, peony, and hydrangea to disclose the unseen behind and beyond the surface. Just by watching, one could not see through the shell of imaginary states; one needs to observe and ponder to rebuild the virtual reality as depicted in “The Matrix.”

Spirituality behind “Hua Fei Hua”

The concept of expressing emotions through objects in Buddhism rituals

Expressing emotions through objects is a method used in literary creations. Through meticulous observations and understanding of certain objects from personal perspectives, one utters his aspirations by depicting objects through a metaphorical technique. Generally, while illustrating objects is an artistic craft, expressing one’s emotions and ambitions is the goal. This is the initial definition of the concept. However, in Wang’s artworks, those beautiful flowers meant to symbolize the human world are inspired by Tibetan Buddhism and the meaning of offerings used in the Buddhism rituals. Born in a pious Buddhism family, Wang Bo-Cheng is exposed to several main Buddhism factions at different levels of understanding. He chooses Tibetan Buddhism because Mahayana Buddhism pays attention to salvaging the mankind in addition to personal liberation. What Wang admires about this preaching is that the Tibetan people consolidate and cooperate, and that they put others before themselves. The eight offerings in Tibetan Buddhism ritual include, “drinking water, bathing water, flower, incense, light, oil, food, and music.” This ritual originates from ancient Indian greeting etiquettes. Kings and guests were offered water to quench their thirst first. Bathing water was then provided to wash dusts off their feet. Flowers were prepared, incenses and candles were lit, oil was to anoint on the body, and people finally were seated to dine. During the feast, performers entertained guests by singing and dancing. Since then, this ritual becomes the symbol of Buddha veneration whose practices are based on these customs. Buddhism has also endowed “water” with eight virtues. Water guides people to follow precepts and make them strong in both mind and body. Its taste surpasses delicacies. It tames people’s tempers as well as clears our souls. It exonerates our sins. It renders us wise words and health. Regardless of rich or poor, water is accessible to all. One could serve at his own wish, from one to hundreds sets of eight cups. Besides, there are Mandala offerings in Tibetan Buddhism which were derived from Indian Buddhism’s “Guhyasamāja Tantras” and the seven scriptures translated by Indian monk Dānapāla in Song dynasty. “Mandala” originally meant observing sun, moon, and Falun to serve Buddha. Since Mandala offerings’ appearance, it also symbolizes Buddha’s altar, the worldview of Buddhism. This worldview consists of Mountain Sumeru at the center and four continents of East, West, South, and North. When serving Buddha with Mandala offerings, the rich could display pearls, agates, or precious medicines and fruits, while the civilians could use sands or pebbles. Similar to servings of eight water cups, Mandala offerings focus more on the convenience of the servers and their introspection.

The eight offerings epitomize an abstract worldview and the origin of rituals in Buddhism thousands of years ago. Wang says he draws the idea of expressing emotions through objects from Buddhism rituals such as the eight offerings and Mandala offerings. Understanding this fact, one could fathom that aside from exquisite textures, why there are only one or few chrysanthemums, hibiscus, peonies, and hydrangea drawn upon the darken background in “Hua Fei Hua.” One could also figure out why the title of this artwork says the flowers on the canvas are not flowers (Fei Hua). In silence, what is left in this world? Anyone embracing great artistic sense could discern the meanings extending beyond the surface that the artist is trying to express. In our daily life, we have already experienced the duplicity in human nature and understood that the value of gifts lies in the heart. Thus, expressing emotions and thoughts through objects is not only seen in Buddhism or literature. However, in Wang Bo-Cheng’s artworks, perhaps the beauty that most people first see or will only see does not connect directly to the connotations hidden behind. Just as the eight offerings do not actually mean those eight cups of water; Mandala offerings do not refer to the actual pearls, pebbles, or agates placed on the plate, these objects are the source for a greater inspiration. We do not probe into the reference of these flowers, and yet we rely on their forms to ponder on the things that go beyond the appearance. Consequently, as mentioned before, the visual analysis in art history would not be proper as a measure to examine this collection. Gin Huang, founder of Gin Huang Gallery, who also practices Buddhism for many years provides a footnote for this solo exhibition that she curates, “I see Buddhist Scriptures in his artworks.” This perfectly points out the fact that how come when appreciating Wang Bo-Cheng’s paintings, we should not see, but instead we should observe.

Artistic Transformation of Contemporary Calligraphy

When asked about the difference between the artistic categories in calligraphy, Wang explains that one is led by the techniques while the other is lead by heart and soul. Wang has learned the art of calligraphy for more than twenty years; thus, his skills and techniques are the medium for expressing the core values in his heart. In his declaration “The Approach of Building Calligraphy” published in 2013, he shared the spiritual representation of contemporary calligraphy. Coupled with his understandings towards calligraphy, arts, and life, Wang finds the balance between performance and re-presentation in the performing arts of calligraphy, which originates from Japan but is popular among all Asian countries now. The name of this declaration has deep meanings within each word. “Building” refers to the process of constructing or de-constructing Chinese characters, and the transformation of ancient words to express modern connotations. Painting calligraphy displays the act of creativity, from how to write the words, to how to compose the images. The “approach” emphasizes to search from within, accumulate one’s life experiences to become the artistic inspirations, and then share them with the public. Wang’s calligraphy is built on visual arts and combined with traditional Chinese paintings. He is particularly skilled at line drawing technique, with which he used golden ink in his past artworks such as “Samsara,” “Be Child,” “Separate the Wheat from the Chaff,” “To Go Far, One Must Start From Near,” “Meaningful,” “Without Overstressing qualifications,” and “Fledge-less.” Golden lines are irregularly arranged, twisted, extended, and diverged. Each piece of artwork is like an individual living organism, with natural beauty and power. In “Hua Fei Hua” collection, Wang applies this sophisticated technique to illustrate the elegance of flowers. Its multi-layer pedals, slender stamens as well as pistils are also delineated. Every line with a style of mannerism resembles a sense, drawing us to fall for it intentionally.

“Hua Fei Hua” collection boasts two stunning features with its application of line drawing technique. The first one is inspired by Wang Bo Cheng’s architectural background. He takes concepts from architectural drawing, which uses lines to form a structure, to add volumes to the conventionally two-dimensional patterns outlined by the line drawing technique. The second feature is drawn from his previous artwork, “In Between,” which explores the spatial composition. The art of calligraphy emphasizes the importance of the blank area. The drawing and the blank area should complement each other, from the structure of the words to the organization of the entire painting. Observing the flowers in “Hua Fei Hua,” one would mistake that petals are filled in with colored ink at first glance. However, when examining more closely, one could see that these petals are in fact the tone of textures. Taking its flat background as the substantial entity, this artwork depicts the flowers with line drawing technique to reflect the depth of the space. The virtual and actual parts in the painting are complementary of one another, which provide a new aspect different from traditionally two-dimensional thinking of line drawing technique.

Another aspect in regards to line drawing that “Hua Fei Hua” addresses is the “changeability” and “concealness” of the lines. Changeability refers to the connection and interaction between the lines. Once the first line is drawn, there is no going back. One stroke connects to another, which presents the relations and tensions between them. It also symbolizes different kinds of relationships human beings have with one another since he was born into this world. As he enters a family, communities, and the society, his relationships with others grow even more complicated. While the network pattern forms from a grid, some leave veins, to a spider web, the desires also grow stronger. To present the works artistically, it seems to be more appealing and expressive to illustrate the true face of lust and ambition. Nonetheless, with the cultivation of Buddhism and calligraphy, Wang is able to view all the desires in life with a calm balance. The desires may always be there. Yet, to transcend beyond those superficial substances is the way to a pure heart.

Text│Lu Xue-Qing